Some of you no doubt have attended a children’s Christmas play recently. Your child may have portrayed Mary or Joseph. Perhaps you have a grandson who dressed in your bathrobe as one of the three Wise Men. Maybe you made an angel costume for your niece. Your kid may have even dressed up like a donkey. But God forbid your child should ever get the villain’s role—the part of the coldhearted innkeeper who turned away the desperate couple on that starry night long ago!

Some of you no doubt have attended a children’s Christmas play recently. Your child may have portrayed Mary or Joseph. Perhaps you have a grandson who dressed in your bathrobe as one of the three Wise Men. Maybe you made an angel costume for your niece. Your kid may have even dressed up like a donkey. But God forbid your child should ever get the villain’s role—the part of the coldhearted innkeeper who turned away the desperate couple on that starry night long ago!

As a father and a pastor, I’ve seen my fair share of live manger scenes and children’s pageants, and I have the videos to prove it. But also, as a pastor given the responsibility to preach biblically to my congregation, I am confronted annually with a problem. Let me pose the problem in the form of a question. Are children’s Christmas plays faithful to the biblical stories of Christ’s birth and childhood?

Let’s make a quick check of the characters, props, and staging for your typical kid’s Christmas pageant (and your live nativity scene, too, for that matter):

Do I have the cast of characters correct? There is the Baby Jesus (usually a doll), Mother Mary, Father Joseph, Wise Men, Shepherds, Angels, a Donkey, Sheep, Camels, and other Extras like maybe an ox, a goat, or duck.

Are these the right props? There’s a wooden stable in a field, hay on the stable floor and all around, a wooden manger in the center of the stable, three gift boxes for the Wise Men’s gold, frankincense, and myrrh, maybe some shepherd’s staffs, a bright star above the stable, and perhaps a backdrop showing Bethlehem on a hill in the distance beneath a starry deep blue sky.

Places everyone: Mary kneels next to the baby in the manger (holding the baby is optional). Joseph stands by her. Shepherds gather (with sheep) on one side of the stable. Wise men gather (with camels) on the other side. Angels hover over the stable. And where you put the donkey (or other critters) is optional.

Now, if I’m not mistaken, the Christmas play version goes like this: Joseph and Mary are forced to travel from Nazareth to Bethlehem because of a census. Mary, nine months pregnant, rides a donkey in great discomfort. She goes into labor before they reach Bethlehem in the middle of the night. Knowing no one there, and having no one to stay with, they go to the local inn. But the innkeeper has no vacancies. Joseph searches in desperation for a place for Mary to have her child. They are forced to go back into the countryside where they find a wooden stable in a quiet field. Mary has the baby there, wraps him in swaddling clothes, and lays him in a hay-filled wooden manger. Shepherds arrive. They were given a sign by angels that led them to the child. Wise Men arrive. They had followed a star.

That’s the story I learned growing up. I hold it dear and know it by heart. I taught it to my kids, and so did many of you. This is what I call the G-Rated version of the nativity. I certify it "Safe for Children."

But there’s another version of the birth of Jesus. It’s an adult version. And it’s in your Bible. Mature students of the Bible should know that much of our familiar Christmas play scenario is biblically inaccurate. My job in this article is simple. I’m going to demonstrate the biblical story of Jesus’ birth. I’ll show you that the biblical story and the Christmas play are quite different.

Matthew and Luke’s Gospels are the only two books of the Bible that offer us information about Jesus’ birth. (Matthew 1:18—2:23 and Luke 1:1—2:40) Matthew and Luke and kids’ dramas agree that Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea. The differences, however, begin immediately.

Our Christmas play has Mary and Joseph leaving Bethlehem proper to find a stable out in the fields. This contradicts Matthew and Luke. Luke 2:8 records that it is the shepherds, not Mary and Joseph, who were out in the fields. And Luke 2:11 and 2:15 and Matthew 2:1 record that Jesus was born in the City of David (Bethlehem of Judea). The shepherds go into town to find the baby. The manger in which Mary laid Jesus is downtown, not out of town.

Luke 2:15 When the angels went away from them to heaven, the shepherds said to one another, "Let us go, then, to Bethlehem to see this thing that has taken place, which the Lord has made known to us."

What about the stable? Neither Matthew nor Luke record that Jesus was born in a stable. The Bible mentions no stable at all. There’s nothing about what a 1st century Jewish stable might have looked like, what it was made of, how it was used. If the birth took place in a stable, the stable was in downtown Bethlehem. But where? Would you find them next to Jewish houses? What were they made of? What did they look like? Archaeologists say that many houses in Bethlehem from Jesus’ time were built on top of caves. They were multi-level homes. The many caves there were used as water cisterns, grain silos, and, yes, stables. Bethlehem, Nazareth, and other first century towns studied by modern archaeology reveal that precious animals in certain times of the year stayed in peoples homes—in a back room or a cave beneath the house. From the earliest times a cave in Bethlehem has been identified as the place of Jesus’ birth (pictured).

There is no competing site. There is no memorial wooden frame in a field somewhere outside of modern Bethlehem. But in downtown Bethlehem there is a first century manger carved into the wall of a cave that for millennia has been venerated as the spot. Built over the cave is the oldest functioning church building in the world, the Church of the Nativity (pictured). (Some scholars speculate that Jesus was born in Nazareth or Bethlehem of Galillee. This contradicts the biblical accounts, but these scholars do not feel that the biblical birth narratives are historically factual anyway. They see Luke and Matthew’s accounts of Jesus’ birth as literary creations by the early church.)

What about the manger itself? Luke 2:7 records that after his birth, the infant Jesus was laid in a manger. Phatne is the biblical Greek word that Luke used; it means animal feed trough. But

again Luke doesn’t tell us what a 1st century Jewish feed trough was made of, or what one looked like, or where one might be placed. Was it wooden? Unlikely. Wood was scarce and expensive in the region, and ancient mangers (feed troughs) are found in many places in Israel from many periods of history including the time of Jesus, and they are made of stone, sometimes standing alone, (pictured with baby) and sometimes set in a wall (pictured).

Perhaps then the ancient tradition in Bethlehem is correct. The 1st century manger in the cave beneath the Church of the Nativity is stone. Perhaps this is the same manger in which Mary laid Jesus.

So where did the wooden-stable-and-wooden-manger-out-in-a-pasture concept come from? The earliest Christian art in the East puts the manger in a cave. But in the West, in Gothic and Medieval Europe, we see wooden stables and mangers in pastures, reflecting the practice of their day, not first century Palestine.

Luke 2:7 is the key verse concerning the exact circumstances of Jesus’ birth. It’s typically translated:

"And she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger; because there was no room for them in the inn." (New International Version)

The key word in this verse is "inn," because there is a problem in translating the original Greek word into English. English versions of the Bible disagree. For example, the New English Bible reads "no room for them in the house." The Bible in Basic English also says "house." The James Murdock Translation reads "no place where they could lodge," and the New Living translation reads similarly, "there was no lodging available for them." The New Jerusalem Bible prefers "no room for them in the living-space." Young’s Literal Translation says "there was not for them a place in the guest chamber."

These variations give us a hint of the translation difficulty here. The Greek word in question is kataluma. How do you translate that into English? Is it an inn, a house, a living-space, a guest chamber, or something else? Well, you may be surprised, even shocked, but "inn" is almost certainly not what Luke meant by kataluma. Let me show you why, and let me show you what Luke much more likely meant.

Kataluma in Luke 2:7 continues to be translated by many Bible publishers as "inn," even though the better translations are "guest chamber" or "living room;" it is translated as such elsewhere in scripture. For example, in Luke 22:11 Jesus instructs the disciples to follow a man into Jerusalem carrying water. They followed him to a house that had a large kataluma where they could all gather together for the Passover. Kataluma is translated in 22:11 in almost all versions as guestroom or guestchamber.

Luke 22:11 And ye shall say unto the goodman of the house, The Master saith unto thee, Where is the guestchamber (kataluma), where I shall eat the passover with my disciples? (King James Version)

They needed a dining room. In the case of this particular kataluma where the last supper took place, Luke clarifies in the next verse that this guestroom was upstairs.

Luke 22:12 And he shall shew you a large upper room furnished: there make ready. (King James Version)

Is there another reason that kataluma should not be translated "inn"? Yes. When Luke means "inn" he uses a different word: pandocheion. For example, in Luke 10:34 is the story of the Good Samaritan. The robbed and injured traveler is taken to an inn.

Luke 10:34 And went to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring in oil and wine, and set him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn (pandocheion), and took care of him. (King James Version)

The Greek term that Luke chooses for "inn" is pandocheion, not kataluma. And the road on which these men traveled—the road from Jerusalem down to Jericho—was a main road. In major towns like Jerusalem and Jericho, on a road heavily traveled, one would expect an inn. A pandocheion. Jesus also mentions an innkeeper in this parable. A pandocheus:

Luke 10:35 The next day he took out two silver coins {35 Greek two denarii} and gave them to the innkeeper (pandocheus). ’Look after him,’ he said, ’and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have.’

So, what’s going on here? Is there an inn in Bethlehem or not? If so, why does Luke call it a kataluma instead of a pandocheion? Why does he mention no innkeeper (pandocheus) at all? And if there was no inn, then what in the world is Luke saying?

First, a tiny village on a minor road would not be at all a likely place for an inn in first century Palestine. Bethlehem was such a place. But if it were a larger place on a main road, Luke would have called an inn there a pandocheion, not a kataluma. And only a pandocheion (inn) would have had a pandocheus (innkeeper).

Second, even if there were an inn in Bethlehem, Joseph would not have stayed in it. Joseph was familiar with Bethlehem. He was of the lineage of David. He almost certainly had family there. It would have been an insult to Joseph’s relatives for him and Mary to stay in a motel when they could provide their homes willingly—and for free. Joseph almost certainly knew the place. He may have even been from Bethlehem. Why do I say he may have been from Bethlehem? Matthew says the holy family probably continued to live in Bethlehem for two years after Jesus’ birth, suggesting that they had perhaps dual residence in Nazareth and Bethlehem. "The house" where they stayed in Bethlehem very well may have belonged to Joseph. (Matthew 2:11)

Third, it’s almost certainly wrong to translate Luke 2:7 as "for there was no room (topos) in the inn (kataluma)." Topos means place, space, or spot, not hotel room. And kataluma means guestroom of a house, not an inn. The correct translation should be:

". . . for there was no place/space/spot in the guestroom."

No place/space/spot for what? Labor and delivery, of course!

Luke is telling us that they moved Mary out of the public area of the house to have her baby in private. Read Luke 2:1-7 carefully. I’m confident that one of the following two scenarios is close to what Luke means:

Sometime after the couple from Nazareth moved in to the guestroom of a Bethlehem relative’s house, Mary went into labor. For privacy and to avoid defiling others (childbirth was considered unclean), she had to move from the guestroom to a basement cave used as a stable. There she gave birth to her firstborn son, wrapped him in strips of cloth, and lay him in a limestone feed trough.

Or:

The couple who had settled in Nazareth returned to their house in Bethlehem. While there, Mary went into labor, but with the guestroom occupied by relatives, they needed a private place for her and the baby, for childbirth was considered unclean by Jewish law. Their house’s basement cave and "corn crib" sufficed.

It’s surprising, but in the Bible, Mary wasn’t in labor on a donkey as a desperate Joseph searched strange streets for lodging. Joseph knew the streets. Mary didn’t go into labor until some time after they arrived in Bethlehem.

Luke 2:5-6 5 He (Joseph) went to be registered with Mary, to whom he was engaged and who was expecting a child. 6 While they were there, the time came for her to deliver her child. (New Revised Standard)

While they were there, the time came. She didn’t go into labor until they were already there for a time.

How did they get there? Joseph and Mary probably traveled on foot from Nazareth. There is no donkey in the biblical story. Can you imagine being a few months pregnant and riding a donkey for eighty miles? If Mary had been nine months pregnant, they wouldn’t have traveled anywhere at all. And Mary certainly wouldn’t have ridden a donkey for the better part of a week while on the verge of labor.

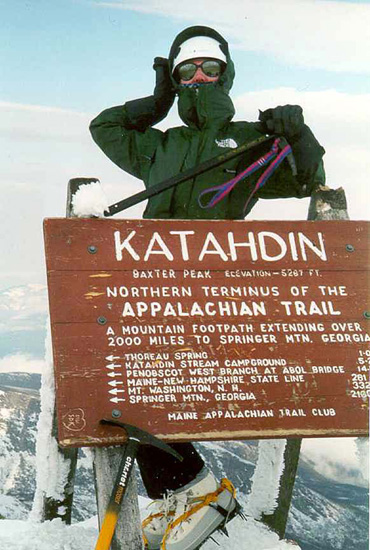

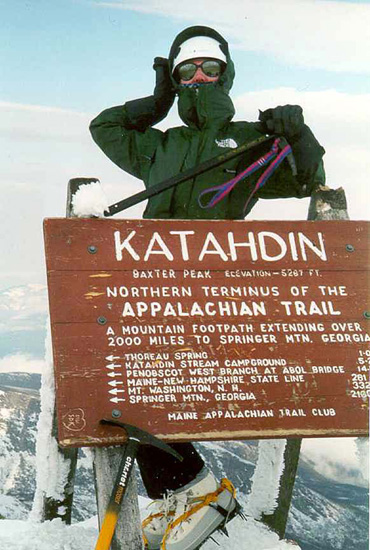

Perhaps Mary was only three to six months pregnant. I know a healthy young woman who in the course of a single day climbed up and down Mount Katahdin (pictured) in Maine while six months pregnant, and without incident. If she had tried to ride up and down Katahdin on a donkey while six months pregnant, however, I suspect there would have been a helicopter airlift.

Perhaps Mary was only three to six months pregnant. I know a healthy young woman who in the course of a single day climbed up and down Mount Katahdin (pictured) in Maine while six months pregnant, and without incident. If she had tried to ride up and down Katahdin on a donkey while six months pregnant, however, I suspect there would have been a helicopter airlift.

It’s a new picture of his birth isn’t it? Mary and Joseph travel on foot from Nazareth to Bethlehem, and though Mary is expecting, they arrive safely without incident. No panic. No desperation. No emergency. Mary was probably too far along in her pregnancy at some point to travel back to Nazareth, so they stayed in Bethlehem with family to await the birth. It was night when the moment came. They undoubtedly lit lamps and moved Mary from the living area upstairs down to a cave beneath the house used as the family stable. You can’t have a baby in a crowded guestroom. Cozy and clean downstairs, Mary gave birth in privacy, thus also avoiding the possibility of defilement in the rest of the house. And as every Jewish mother in that day knew, a manger can be just the right size for a newborn. Mary was not likely the first mother to use a manger for a crib. Most mothers probably did. And Jesus, like every baby, was wrapped in strips of cloth, their version of pampers. His birth, in most ways, was no different than any birth at home in first century Judea.

What about the innkeeper? If there wasn’t an inn in Bethlehem, doesn’t that mean that there was no innkeeper? Yes. The innkeeper in our children’s Christmas plays—the subject of many a sermon on failing to make room in your heart for Jesus this Christmas—never existed. Look in the Bible. He’s simply not there.

What about animals in the downstairs cave with Mary? As I indicated, no donkey is mentioned, but neither is an ox, calf, goat, duck, dove, or chicken. So what about sheep? Luke doesn’t say what the shepherds did with the sheep when they came into Bethlehem looking for the baby. I wonder, however, whether they would have brought an entire herd of noisy sheep into a sleepy village in the middle of the night. I rather doubt it. So there probably were no sheep at the manger either. Perhaps one of the shepherds stayed behind. Or maybe they visited the manger in shifts. So far as the biblical account goes, there were no animals at the manger. (I’ll get to camels in a minute.)

What about the angels? An angel announces Mary’s pregnancy to Mary and Joseph. Luke says it was Gabriel. There are other angels in Luke’s story; they "sing" for the shepherds in the fields outside of town. (2:13-15) [There are only male angels in the Bible (Acts 12:9 for example), and the noun "angel" (aggelos in Greek) is grammatically masculine. Gabriel’s name means "man of God," a masculine name. The other named angel in the Bible is Michael ("who is like God"). If Satan ("adversary") can be viewed as a fallen angel, he would be a third. The Apocrypha names two additional angels: Raphael meaning "God has healed" (Book of Tobit) and Uriel meaning "fire or light of God" (2 Esdras). No angel in Scripture is designated as female, though Zechariah 5:9 possibly refers to female angels.] But no angels appeared at the manger, according to scripture.

What about the angels? An angel announces Mary’s pregnancy to Mary and Joseph. Luke says it was Gabriel. There are other angels in Luke’s story; they "sing" for the shepherds in the fields outside of town. (2:13-15) [There are only male angels in the Bible (Acts 12:9 for example), and the noun "angel" (aggelos in Greek) is grammatically masculine. Gabriel’s name means "man of God," a masculine name. The other named angel in the Bible is Michael ("who is like God"). If Satan ("adversary") can be viewed as a fallen angel, he would be a third. The Apocrypha names two additional angels: Raphael meaning "God has healed" (Book of Tobit) and Uriel meaning "fire or light of God" (2 Esdras). No angel in Scripture is designated as female, though Zechariah 5:9 possibly refers to female angels.] But no angels appeared at the manger, according to scripture.

What about Joseph? Was he present downstairs for the birth of his son? Almost certainly not. Women assisted women in childbirth. Most towns in Jesus’ day had a nurse midwife who was granted priestly immunity from purity laws so as to assist in childbirth without ritual defilement, which saved midwives a trip to the Jerusalem temple after each birth they attended. A midwife, or women with experience, probably helped Mary, though the Bible mentions none. Yet note that the Bible doesn’t mention where Joseph is during Mary’s labor. So the best assumption is that he’s upstairs waiting for word of the health of his wife and his firstborn son. Would Joseph have been allowed down to see them after all was cleaned up and ready? Yes. Luke suggests this is the case. First, Joseph presence is not mentioned in the verse that announces Jesus’ birth.

Luke 2:7 and she brought forth her son -- the first-born, and wrapped him up, and laid him down in the manger, because there was not for them a place in the guest-chamber. (Young’s Literal Translation)

Yet when Luke tells about the visit later that night by the shepherds, he includes Joseph’s presence. Probably Joseph was nearby for the birth, but was allowed to come near afterward.

Luke 2:16 And they came, having hasted, and found both Mary, and Joseph, and the babe lying in the manger, (Young’s Literal Translation)

So, exactly who was there around the baby Jesus? There was at first just Mary and hopefully a midwife, then later came Joseph, then came the shepherds. Is that it? Yes. That’s all.

You may be wondering about the Wise Men, their camels, and the star. These come much later. The Wise Men were not present for Jesus’ birth. Luke mentions no Wise Men, no camels, and no birth star. Matthew does, but what is often overlooked is that the star did not appear until Jesus was born.

Matthew 2:7 Then Herod secretly called for the wise men and learned from them the exact time when the star had appeared. (New Revised Standard)

The Wise Men didn’t begin their journey until after Jesus’ birth. The star appeared to announce that the birth had occurred. The Wise Men did not arrive in Bethlehem until about two years later. How do we know that?

Matthew 2:16 When Herod saw that he had been tricked by the wise men, he was infuriated, and he sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under, according to the time that he had learned from the wise men. (New Revised Standard)

The Magi tell Herod when the star first appeared. He asked them for this information because he wants to know how old the child might be presently. Knowing the approximate age of Jesus, Herod orders every child two and under be killed—though why he orders girls killed too is unknown. So the child, his birth coinciding with the appearance of the star, would have been about two years old when the Wise Men arrived.

Yes, according to Luke, Joseph and family did return eventually to Nazareth.

Luke 2:39 39 When they had finished everything required by the law of the Lord, they returned to Galilee, to their own town of Nazareth.

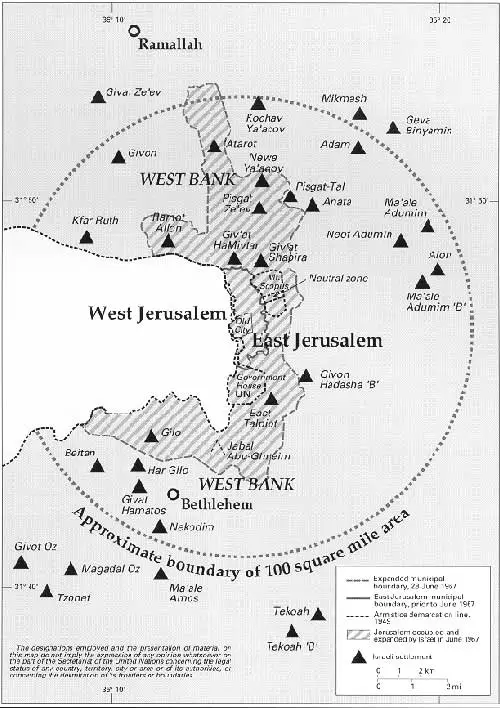

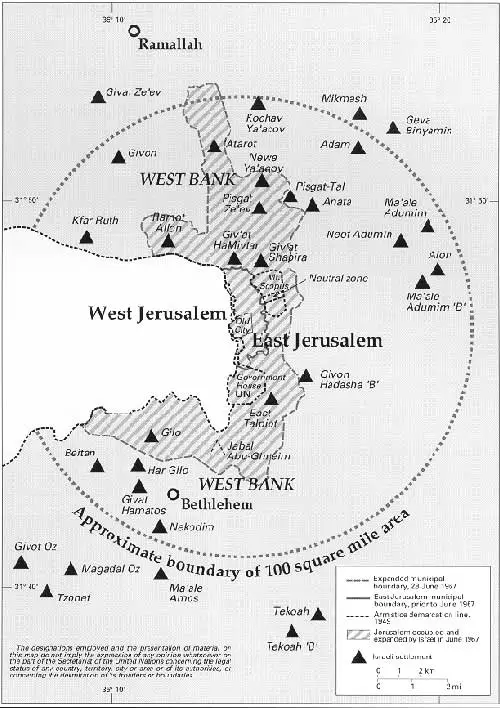

But Joseph, being an observant Jew (Matthew 1:19), would have traveled to Jerusalem for at least the required three annual festivals in Jerusalem. Bethlehem is only six miles from there. So if he had a house in Bethlehem, his new family, coming down from Nazareth to Jerusalem regularly, could have stayed each night of the festivals in their own Bethlehem home. But if Joseph didn’t have his own house in Bethlehem, he and Mary could have accomplished the same thing by overnighting with relatives in Bethlehem during the Jewish festivals. The six miles from Bethlehem to the Jerusalem temple was an acceptable walking distance. (pictured—note Bethlehem within circle, lower left)

Six miles sounds like a long walk today, but Joseph probably walked to work in Sepphoris (Zippori in Hebrew) eight miles round trip from Nazareth every day. (There was excellent employment in Galilee’s new capital city for a builder; this may have been why Joseph relocated to Nazareth in the first place.) Twenty miles a day was considered a full day’s walk. And, other than riding an expensive animal, what choice did working-class people have but to walk?

It’s a biblical fact that the holy family returned to Nazareth eventually. (That was their primary residence. He is called "Jesus of Nazareth.") But it is also a biblical fact that when the Wise Men showed up two years after Jesus’ birth, they found Mary and the baby in "the house" in Bethlehem. (Matthew 2:11) Perhaps they were lodging in Bethlehem for one of the Jerusalem festivals when the Wise Men arrived. If it wasn’t a relative’s house, it was probably Joseph’s own house, the very same house beneath which Jesus was born.

Matthew adds that the holy family had to hide from Herod for a while in Egypt. When Herod died (4 B.C), they wanted to return to Bethlehem (again suggesting that they had a house there), but Herod’s son Archelaus was on the Judean throne, and he was worse than his dad. So they went home to Nazareth. By that time, Jesus may have been about six years of age, old enough to be learning his father’s trade.

Back to the Wise Men, the biblical Greek word for Wise Men is Magi. Our English word magician comes from the term Magi. These men were eastern intellectuals skilled in science, astronomy, astrology, dream interpretation, and magic. Some are portrayed positively, like the Magi that brought the toddler Jesus gifts. Others, like the Magi Simon of Samaria (Acts 8:1-24) and Bar-Jesus of Cyprus (Acts 13:1-12), are portrayed negatively. Magi could be found not only in Arabia, but also throughout the Roman Empire.

Matthew doesn’t tell how many Magi visited toddler Jesus. Guesses range from two to twelve. Nor does Matthew say how they traveled. No camels are mentioned. It’s doubtful that there would have just been two or three, however, due to the danger of travel and the value of their cargo. It may be appropriate to think of a dromedary. There is safety in numbers. The Bible doesn’t give the Magi’s names or their races, though coming from "the east" we can assume they are Arabian. One scholar I know believes they were Nabateans familiar with the spice route that took them through Petra to Gaza regularly. But speculation about their names, their race, and their number come from later legends, not the Bible. What Matthew makes clear is that they brought gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Is there any significance to these gifts? Perhaps. Gold was a typical gift for a king. Frankincense was a typical gift for a priest. And, strangely, yet prophetically, myrrh was used for cleaning and anointing corpses. Myrrh was typically a gift for a death in the family.

Where was Jesus born? Probably in a cave beneath Joseph’s own house in Bethlehem. In the Bible there is no inn, no innkeeper, no desperate search for a room, and no one in labor on a donkey. Who comes to see Mary and the baby in the manger? Joseph and shepherds come. No animals, no angels, no Wise Men. Two years later, probably in the same Bethlehem house, two or more Magi come bearing gifts for Jesus, now a toddler.

In the course of this article, I’ve shown that several people, animals, and elements in the Christmas play version are not found in the Bible. On the other hand, there is a biblical character who cannot be found in the typical Christmas play. The true bad guy is King Herod the Great. He’s missing from theses kiddie events, no doubt, because his order to slaughter all of the innocent babies and toddlers in Bethlehem is neither G-Rated, nor does it evoke holiday cheer. (pictured) So, I suppose a kinder and gentler bad guy was invented by well-meaning playwrights, one who isn’t in the biblical text at all, but still serves his purpose as the villain: the hardhearted innkeeper. And Herod, the true, lying, paranoid, murdering, biblical bad guy, is omitted.

In the course of this article, I’ve shown that several people, animals, and elements in the Christmas play version are not found in the Bible. On the other hand, there is a biblical character who cannot be found in the typical Christmas play. The true bad guy is King Herod the Great. He’s missing from theses kiddie events, no doubt, because his order to slaughter all of the innocent babies and toddlers in Bethlehem is neither G-Rated, nor does it evoke holiday cheer. (pictured) So, I suppose a kinder and gentler bad guy was invented by well-meaning playwrights, one who isn’t in the biblical text at all, but still serves his purpose as the villain: the hardhearted innkeeper. And Herod, the true, lying, paranoid, murdering, biblical bad guy, is omitted.

Perhaps you’re worrying about what to tell your children now. I suggest you allow them to keep and enjoy their colorful cast of characters from the Christmas nativity plays . . . for now. Plays and nativity scenes introduce them to the basic story. They learn some of the characters. And though what we present them isn’t super-accurate biblically, the Christmas pageants and popular manger scenes serve a well-intended purpose. They engage the imaginations of our children and involve them in the story. I think parents should teach their children the adult version only when they think the children are ready.

P.S.

There is a similar biblical discrepancy with Jesus being a tekton. "Carpenter" is the popular but inaccurate translation. Sorry. The Grinch stole Christmas, and now he’s going after our beloved carpenter shop!

Nevertheless . . .

Tekton means "builder." It’s the root word for tectonics, which is the study of the earth’s crust or the science of constructing sky scrapers. Last time I checked, the earth’s crust and sky scrapers are not made of wood.

Add to this the fact that in the Bible Jesus never spoke of carpentry once, but spoke often of building and stone, giving the picture of a "mason" instead of a "wood worker."

Besides, wood was scarce and expensive. (The first century boat excavated on the shore of the Sea of Galilee in 1986 was constructed with wood from eleven different kinds of trees demonstrating how boat builders scrounged whatever scraps of wood they could find so to recycle them in boat construction.) How do you feed your family in the landlocked village of Nazareth (Population: 200) by making the occasional spoon or yoke? You can’t. But a builder might do well living near a large construction site. Nazareth was near such a site: Zippori (or in Greek, Sepphoris).

Joseph and sons from Nazareth could have walked to Zippori everyday--Galilee’s capital during Jesus’ growing up years, just four miles away--to work at one of the largest construction project sites in the entire Mediterranean basin at the time. Herod Antipas was building a new capital city for Galilee. Lot’s of work. Good pay every day for a skilled, local builder and his sons.

But if a Bible publisher dared change "carpenter" to "construction worker" or "craftsman" or even "master builder," he would likely be punished with bad sales.

"How dare they take Joseph’s carpenter shop away from us?"

And likewise, were more translators to begin translating kataluma as something other than inn . . .

"How dare they take the innkeeper and his inn away from us?"

My suspicion is that tradition will retain the inn and the innkeeper. Tradition will demand that Mary ride her donkey in labor, that three Wise Men go to the manger, and that Joseph teach Jesus how to be a carpenter. Traditions are not easily changed.